"Who won the San Francisco earthquake?" This question truculently put by the gentleman from Texas, ended summarily a rather pointless performance on the part of a fellow member of the Military Affairs Committee of the House. True to his warlike instincts the latter had engaged at length and loudly in browbeating a witness before the Committee, Jeanette Rankin, herself a former representative, now one of the most effective advocates of peace in the United States. Climaxing a patriotic flight the gentleman shouted at the lady: "Who won the World War?" And received the above classic answer to his question in the form of another question, itself in a way as devastating as an earthquake. To make the irony of the affair more complete the Honorable Maury Maverick, who thus closed the incident, comes from the bustling city of San Antonio, Texas, which happens to be one of the greatest military centers in the world, if indeed it is not the greatest.

On another occasion when the news of Hitler's burning of the books was still fresh, Charles A. Beard, dean of American historians, was being interrogated before the same Committee, although the word "heckled" would describe the process more accurately. Because of his partial deafness the eminent scholar was at a marked disadvantage. Scenting an easy kill, one of the more militaristic members of the Committee started in full cry, his eyes gleaming, his nostrils quivering. And the object of his relentless pursuit? Ah, my friends, it was COMMUNISTIC LITERATURE, nothing less—and nothing more definite, either. He wanted to know all about it; in fact he clamored—and yammered—at great length for knowledge, meanwhile doing his utmost to browbeat the witness. Most of all he craved to learn in what libraries such dastardly literature was concealed. Whether or not the Professor grasped this particular question, his mild answer was: "In all of them, I should think." To which Maury Maverick added, again ending the séance: "No doubt there's plenty of it in our own library, the Congressional Library. Does the honorable gentleman desire to have it burned down also?"

Unquestionably, given a good cause, the gentleman from Texas dearly loves to upset the apple-cart. And nothing affords him more joy, holy or unholy, than to deflate stuffed shirts, especially when enveloped in military uniforms, as sometimes happens to be the case. In so doing, of course, Maverick runs the risk of gaining the reputation of an enfant terrible, or, worse still, of a recognized congressional wit. The latter is, perhaps, the saddest of all legislative fates, as the career of "Sunset" Cox demonstrated a generation ago. That the gentleman from Texas has escaped such a nemesis is not due to any lack of humor, mordant or otherwise. It is due to the fact that he does not stop with the outburst of ready laughter. Attack with words, whether humorous or with "tough, hard, mean words"—to use his own expression—is always backed up by serried masses of facts, laboriously collected, meticulously ordered. And facts are also "tough, hard, mean" things. To illustrate and at the same time to revert to the two incidents narrated above Maverick kept up the fight until he had killed the Military Disaffection Bill. He is still prouder of that success than of anything else he has accomplished in Washington. And that in spite of many notable achievements which bulk much larger as matters of public business and which have reverberated resoundingly through the press of the country as a whole. For example, his fights for the conservation of natural resources—the matter which is always foremost in his thought, for housing and slum clearance, for the TVA, for mandatory neutrality legislation, and more recently for the reform of the Supreme Court are not likely soon to be forgotten.

Maverick was born at San Antonio, Texas, October 23, 1895, the eleventh and youngest son of Albert and Jane (Maury) Maverick. English, Scotch-Irish, and French Huguenot stocks—a strong and typically American mixture—are all represented in his ancestry. It is impossible to talk to the Congressman for any length of time without discovering that he is enormously interested in the history of his family, a trait which, by the way, is abundantly manifested in his recent book, A Maverick American. At first sight it would seem to indicate that the gentleman from Texas shares the aristocratic outlook supposedly cherished by all members of "fine old Southern families." Twitted on this score, so incongruous with his extreme democratic outlook, Maverick defends himself with a certain show of indignation. He assures you that he is "an ordinary man with ordinary ideas" (which, with all due regard to his sincerity, is simply not the case); further, that so far as he can discover all his ancestors were of the same type. In other words, all the Mavericks were mavericks, i.e., commonplace men and women more or less astray in the midst of the social and economic forces of their time. Regardless of the tie of blood the Congressman assures you that he can see their vices and failures just as clearly as he sees their virtue and successes. Finally—and make no mistake about it—he studies their past struggles not because of any aristocratic feeling but solely for his own guidance amid the dominant forces of the here and now.

An ingenious theory, this, to dispose of the charge of ancestor worship. Nor can it be dismissed out of hand as rationalization, pure and simple. Still it is apparent that Maverick admires his forbears as a whole, particularly those who were on the popular side in the political conflicts of their day. Unquestionably also he takes a certain sinful pride in their fighting qualities, regardless of the side on which they fought. Chalking up this minor demerit—if demerit it be—against the Congressman, it must be admitted in his favor that his extended genealogical researches have given him an unusual knowledge of the history of the country and particularly of the South as seen from the viewpoint of human mavericks. Whether his ancestors were conservatives or radicals—mostly they were the latter—it is true that he studies them always from the point of view of the problems he is trying to solve today. One of the most characteristic features of A Maverick American is the way in which the author after describing briefly the exploits of some colonial or revolutionary ancestor, proceeds to apply at length the lessons thus learned to the matters he has now in hand, for example, to soil conservation, militarism, taxation, poor relief, and the like. Decidedly Maury Maverick is a much more effective and a much more down-to-the-minute political leader because he has forgathered so extensively and so intimately with his forbears.

In his political career the Congressman is under particular obligation—as will appear later—to his grandfather, Samuel Augustus Maverick. It was because of this gentleman's easy-going management of his ranch that the name "maverick" came to be applied to unbranded, roaming cattle. To his father and mother, however, Maury's indebtedness is beyond all computation. They seem to have been ideally fitted for parenthood; moreover they had had plenty of practical experience in child psychology before the birth of their eleventh and last child. In the charming picture which the son paints of their life together, characteristically using political colors, the mother is portrayed as a shrewd and active prime minister, the father as a quiet and kindly constitutional monarch. Tolerance reigned in their household; frankness and fearlessness were the order of the day. Here the twig was bent; so the tree is inclined.

Educational life on the whole proved much less satisfactory than family life. Young Maury came up through the public grade schools and the High School of San Antonio; for some reason undisclosed he notes: "did not graduate from the latter." Indeed he seems to have made a specialty, then and latter, of dodging graduation. Which, of course, now leaves him wide open to the offer of an honorary degree. (Which, probably, he would decline.) There was a rather ineffectual year at Virginia Military Institute; after that, three "wasted" years at the University of Texas, where he enrolled for journalism. Again the notation: "did not graduate." This time the reason was that Maury found himself overpowered by a desire to practice law, probably with some thought of politics in the offing. As a result he set himself the strenuous task of doing the three years' work of the law school in one year. And a third time he "did not graduate." However, he won admittance to the local bar and threw himself into practice with the ardor characteristic of him when he is really interested in what he is doing.

One of the commonest obsessions of college men who have reached middle life is that during their undergraduate year they were regular hellicats. As a moral equivalent or sublimation for raising Cain after the time for that sort of amusement is over and done, this trick of memory probably has a certain ethical value. Curious, however, that a man so shrewd as Maverick should be subject to it. As foundation for the delusion he adduces nothing more conclusive than the usual catalogue of student sins—cutting, activities, college politics, membership in an organization known as the Campus Buzzards, drinking, brawling and disorders on the campus, run-ins with the deans, and so on, and so on. (No mention of "fussing." Why not? Texas was coeducational.) On the other hand, Maverick admits that during his high school and college years he was an omnivorous reader, particularly of "banned" books. As this was before the days when sex was discovered apparently these latter were for the most part treatises on ethics, philosophy, and sociology of which professors disapproved. Or said they disapproved. Experienced college instructors will recognize the device, which is at least several centuries older than Machiavelli. As they well know, nothing so whets the curiosity of an undergraduate as to tell him that he ought not read a certain book. Whether so intended or not in the present case, young Maury swatted up vigorously all prohibited literature; thus even when in college his education was largely self-administered. Evidently his intellectual curiosity was insatiable. Given a really understanding tutor he would have forged ahead at a tremendous intellectual pace. As things were, he did indeed make direct use of the instruction given him in journalism. On the other hand, he took no courses in economic or political science. Owing to his prejudice against professors Maverick is rather loath to admit being influenced by any of that tribe. Under pressure, however, he does pay handsome tribute to Edwin DuBois Shurter, now retired, whose instruction in public speaking, particularly in the matter of logical and effective presentation, has been of the greatest possible utility to him throughout his political career. And in general Maverick acknowledges the value of university training even if most of the courses in his time were dull and tiresome. One detail of his educational experience is not without distinct political significance. Since the University was located at Austin, students had an excellent opportunity to observe state government in action; also to meet personally the present and prospective leaders in Texas affairs. As a piquant detail he notes that many members of the legislature were attending the law school, adding "so we frequently attended the State Legislature."

It was by no means certain that Maverick was predestined to politics, highly gifted for that pursuit as he has shown himself particularly since entering Congress. Various other alternatives were first explored and eliminated. Thus he might readily have gone on with journalism for which he was trained at the University of Texas and which undoubtedly he would have been brilliantly successful. Already at the age of eighteen he had secured a temporary job as city editor of the Amarillo News which he enjoyed hugely. After completing his work at the University he made rapid progress as a lawyer and was elected, partly as a result of his popularity among younger members of the profession, partly because of some shrewd political maneuvers, president of the San Antonio Bar Association at the age of twenty-four. It is clear, however, that the detail of legal practice is as repellent to him as it was to the young Theodore Roosevelt, whom he resembles in many other respects. Moreover he did not like the idea of prosecuting criminals; he "always felt sorry for the defendant." One other profession to which he devoted himself temporarily, that of the soldier, would have proved impossible in the long run. For an individual so wholly dedicated to the love of liberty as Maverick is, life under military discipline is unthinkable. Nevertheless he enlisted promptly after our entry into the World War, served with distinction as lieutenant of infantry in France until desperately wounded, October 4, 1918, and was awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart medals for gallantry in action. Of this experience, to which he devotes thirty of the most poignant and brilliantly written pages of A Maverick American the principal results were the knowledge of war and the hatred of it which are the strongest of his intellectual and emotional drives to the present day.

Following his excursion into legal practice Maverick discovered, somewhat to his own surprise, that he was a business man of sorts. He made money hand over fist in lumber and building; indeed his conscience troubled him not a little at the ease with which he could run up jerry-built houses for $800 or $1000 and then sell them out of hand for twice as much. Quite apart from such scruples, however, it is clear that wealth makes little appeal to him. From his successful building experience, however, Maverick did derive one result of permanent political value, namely a thorough practical knowledge of the housing problem in the United States. And that problem has ranked high among his preoccupations as a public man ever since.

Considering the number of vocational bypaths Maverick explored, one may well ask: "Why, then, the ultimate decision to enter politics?" Partly, as we have seen, because of ancestral tradition. It cannot be maintained, however, that immediate family environment predetermined his choice. True the Mavericks had the advantage of being "old settlers"; moreover it is not without political significance that the Congressman himself has maintained a residence in the San Antonio district throughout his entire forty-two years, and in his present residence for ten years. Of living relatives, however, only one, an uncle by marriage, had been a congressman. There was, of course, the glowing memory of the grandfather, Samuel of cattle fame, as a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence back in 1836. While other more distant relatives had held local offices on up to a governorship or two, still the great majority of them had been soldiers, sea captains, merchants, and plantation owners.

As to the dawn of political consciousness Maverick is quite definite. It occurred at the age of six when President McKinley visited his home, evidently making a tremendous impression on the boy. Subsequently he was to meet Bryan under his father's roof, and elsewhere La Follette, Victor Berger, and Eugene Debs, all of whom he admired apparently in proportion to their radicalism and forthrightness. And, of course, he met many Texas worthies including "Pa" Ferguson, who despite his demagogy "had a heart" and also the guts to fight the fire of the K. K. K. with an even hotter backfire; also George C. Butte, professor at the law school of the University, whom Maverick was to support some years later in his candidacy against Ferguson. Undoubtedly this range of political acquaintance, extremely wide for one so young, was potent in turning his thoughts toward a public career.

If the young Texan was predestined to politics it was, however, neither family, nor education, nor acquaintance which decided the matter. Rather he was driven by his social consciousness, or, to avoid professorial words abhorrent to the Congressman let us say he was overpowered by the true maverick spirit, namely by deep sympathy with the multitude of those who were astray and neglected. The most distinctive thing in his whole earlier life was his assumption of the role of a hobo during the last years of the Hoover regime when there was no relief and when, as a result, thousands of "transients"—human beings, not lost cattle—were drifting aimlessly and in dire misery through the vast reaches of Texas. To study their plight he dressed the part, not a hard job for him; he lived with them in "jungles" and flophouses and on the open road, incidentally becoming lousy in the process. But he did not stop with the mere accumulation of sociological data. Acting on what he had learned at first hand, he established a co-operative colony for transients at the edge of San Antonio which did excellent work until government relief began. In itself this experience may have been of minor importance. But it is vastly significant as to the springs of action which move Maverick. In times of profound distress a man with his deep humane feeling simply must leave all else and go into politics in the effort to set things right.

Second only to this fundamental emotional drive, Maverick had to go into politics because of the urgings of his intellect. Nourished by ceaseless reading of economics and political science, he knows that he can set things right, some things at least, if power be given to him. And he means to do all that is in him to that end regardless of opposition and objurgation. Those mistake the man utterly who point to his alleged demagogy as a basic trait of character. "I may demagogue," he observed, using the word as a verb after a fashion coming into vogue in Washington, "but never on any matter of importance." Really all that it means to him is nothing more than an occasional resort to sensationalism in order to arouse interest and secure support. Back of all such superficial manifestations there is a cool, disciplined, and informed intelligence of the highest order. Also an inflexible determination to tell the truth and shame the devil, regardless of the cost to his own political career.

No doubt it will grieve the Congressman sadly, but it must be said that, much as he affects to deride professors, he possesses many traits of that species. True he does not speak their "jargon"; that would never do since he has to run for office from time to time. But he does read their books continually, translating them into bills, also into speeches for both congressional and popular consumption. [For example, his H. R. 7325, 75th Congress, 1st Session, introduced June 1, 1937, providing for the creation of an Industrial Expansion Board and other Federal agencies, represents a painstaking effort to create the administrative machinery necessary for the carrying out of the principles of Mordecai Ezekiel's profoundly significant book entitled $2500 a Year.] He does work the Congressional Library overtime, particularly the Research Division. He does write book reviews, even publishing them to the Congressional Record. He does contribute frequently to such high-brow journals of opinion as The Nation and The New Republic. He does call continually upon braintrusters for research assistance, sometimes putting two of them at work, unknown to each other, on the same problem in order to compare their findings. He does annotate his short, short speeches with long, long footnotes full of details, a professorial habit if there ever was one. He does make the damaging admission in A Maverick American that "the march of the professor is the greatest advance in the history of our government." Finally, as the Swarthmore address showed, he does love to talk to students. It was, in fact, a typical academic lecture even to the characteristic fault of such discourses, the effort to cover too much ground. Also Maverick sent several thousand public documents to the College beforehand, asking that they be distributed to students in preparation for his speech. In other words, professorial words, "collateral reading" if you please.

Although he had interested himself in civic affairs for several years Maverick's actual entry into politics did not occur until 1929, when he ran for the office of tax collector. To the surprise of the wiseacres he was successful against a city-county machine previously considered impregnable. Two years later he won his re-election against the same opposition. It is rare indeed that the personal popularity of tax collectors increases during their term of office. Nevertheless in 1934 Maverick was elected to Congress after two bitter Democratic primary campaigns in which he defeated the Mayor of San Antonio. Again in the primaries of—final elections being virtually uncontested south of the Mason and Dixon line—Maverick received a vote nearly equal to that of his two opponents combined (Maverick, 21,703; Seeligson, 14,378; Menefree, 7,606), and a plurality twice as large as that by which he had won the nomination two years earlier. These figures are the more remarkable because the San Antonio district, unlike the overwhelming majority of those in the South, has been carried by Republicans at least half the time during recent decades. [In the primary of July 26, 1938, Maverick was defeated for renomination to Congress by an eyelash, his vote being 23,584 to 24,059 for his opponent. Perhaps the most striking feature of his campaign was the large amount of publicity it received throughout the country. It is seldom indeed that a mere congressional primary is thus treated as a matter of national interest. Maverick made a strenuous fight and took his defeat philosophically. To him it was merely the end of a round, not the end of the battle. Given his ability and energy one may confidently expect him, after a brief, well-earned rest, to resume his activities upon the stage of national politics.]

Maverick's campaign for the congressional nomination in 1934 took all the money for expenses that he could lay his hands on up to the legal limit of $2,500. Doubtless also friends spent something in behalf of his candidacy, how much he does not know. In his second campaign expenses were negligible. While contributions were made both in 1934 and 1936 by well-wishers and relatives, none were received from corporations. As noted above there is seldom much of a contest down South in final elections; hence the Federal Corrupt Practices Act is of even less importance there than elsewhere. In general Maverick believes that it is either not strong enough or not sufficiently supported by public opinion to insure absolute enforcement.

One incident of the first campaign for Congress is decidedly worth recording. As a result of the severe injury to the back and spinal cord which he received in France, Maverick had been in and out of hospitals more or less for sixteen years. On various occasions when supposed to be unconscious he had overheard surgeons predict his early death. Often he suffered from acute pains which made him unsteady on his legs. Although he was then on the water wagon it was perhaps only natural under the circumstances that his opponents should denounce him as a drunkard. Maverick did not deny the charge, believing it would do him less harm than a true statement concerning his precarious physical condition.

Whatever else may be alleged against him Maverick is anything but a machine politician. Asked to state in writing the importance he attaches to party committees—state, congressional, county, city and ward—his answers were five straight "None's." Nor is he a member of any such committee. On the contrary, as we have just seen, he was opposed solidly by them, as well as by all the newspapers of the district, every time he ran for office. Also by the majority of big business men, especially the crooked oil operators; by all bankers save one; by "carpetbaggers," who are now of the corporate rather than of the old-time political variety; finally by nearly all those who because of wealth or prominence think themselves "big-shots," with or without foundation in actual personal achievement. On the whole a rather formidable opposition. As against it Maverick has the backing of a powerful Citizens League which he was instrumental in organizing. Further he has the support of a small number of big business men—big, that is, not only in amount of capital invested but even more so in the breadth of their social and economic vision. Of the manufacturers he estimates that some thirty per cent are for him; also a large proportion of the grocerymen, druggists, and small tradesmen and middle classes generally; and a still larger proportion of the poorer voters. Finally it is a matter of common knowledge that the masses of Mexicans of the San Antonio district swear by him. Evidently Maverick is as fond of them as they are devoted to him. Contrary to the practice of many politicians who think it a shrewd vote-getting device to address naturalized constituents in their own tongue, the Congressman, although fluent enough in Spanish, has always made it a point to talk to his friends from below the Rio Grande in English and to treat them in every way as full-fledged American citizens. Reckoning up all the friendly forces listed above, Maverick estimates that from thirty-five to forty per cent of the voters of his district are for him in spite of hell and high water. His task in campaigns, therefore, is to rally the additional ten to fifteen per cent necessary to victory.

Nor is Maverick much more interested in patronage than he is in other aspects of machine politics. After all, getting jobs is the business of lordly senators rather than of mere representatives. If Civil Service examinations stand in the way of applicants Maverick is heartily glad of it. He has asked for very few political appointments, and these chiefly for constituents who were in dire need. And he is much more deeply interested in remedying economic conditions so that there will be jobs for all than he is in spoils of any sort.

Nor, finally, is Maverick a "joiner." Membership in the Masons or Moose, in the Eagles or Owls, does not allure him. Quite apart from the ethics of the case, he regards the mixing of secret societies and politics, i.e., peanut politics, as not worth the trouble involved. While an undergraduate at the University of Texas he did join a fraternity; now, however, he is inclined to believe that, because of their inherent snobbishness, such organizations might well be abolished. Curiously enough considering his strong anti-militarist views, he has retained membership in the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, largely, he explains, "for sentimental reasons." But he has been an active, fighting member, from conviction, of the American Civil Liberties Union ever since his return from France in 1919. Perhaps as a result of the survival of the boy in him he belongs also to the Circus Fans of America and is a director of the San Antonio Zoological Society.

Emphatically Maverick does not belong to that school of statesmen who take the weight of public opinion by piling telegrams, pro and con, in separate stacks and voting according to whichever turns out to be the higher. Contrary to the insinuations of Washington newspaper men, it is doubtful whether any congressmen follow this procedure habitually. A certain justification might, however, be found for stacking telegrams—in the wastebasket—on occasions when public utility corporations have kept the wires to Washington hot with thousands of messages manufactured to order in their own interest. However this may be, Maverick devotes a considerable part of his time to keeping in touch with his constituents. Thus when the Supreme Court fight was at its hottest a pile of clippings fresh from the newspapers of the Twentieth Texas District was constantly before him. One bundle bore the following comment from a local observer: "'Great Mass Meeting' last night. Fathered, mothered, and sistered by A—B—, X—Y—, and a few other 'Jeffersonian Democrats.' Attended by less than two hundred, half of whom were curiosity seekers."

Further, as part of the process of keeping in touch with constituents Maverick gives the most careful attention to his correspondence. He admits that its volume is ungodly; he receives requests continually for advice on subjects ranging all the way from obstetrics to theology from men and women in every walk of life. Notwithstanding the amount of letter writing involved the Congressman enjoys it, particularly when controversial in character. An early masterpiece of his along the latter line achieved national publicity and caused a country-wide roar of laughter. To a particularly stupid, abusive and long-winded correspondent he replied on official stationery, in full form with address and signature. However, the body of the letter consisted of one word only, viz, "Ph-h-h-h"!

"A soft answer turneth away wrath" but it is not news. On the other hand, while "grievous words stir up anger" they often make the front page. The Congressman realizes this keenly, as the most cursory study of his correspondence reveals. To a "gentleman" in a remote city who had written calling him "an ass," his speeches "hooey," and his legislative activities "mere hocus-pocus," Maverick replied: "Your thoughtfulness, your kind-heartedness, and particularly your courage in writing me from such a distance, overwhelm me."

A persistent epistolary heckler from Amarillo, arguing the matter of soil conservation in what Sir Henry Maine once described as "weak generalities and strong personalities," denounced all congressmen as "opportunist politicos full of fanciful notions," whom "we pay $10,000 a year for being wooden Indians and messenger boys instead of statesmen"; adding sundry other chunks of verbal garbage too noisome and too numerous for quotation. Firing back at this human stinkpot Maverick wrote: "I thought that I had insulted you enough in my last letter. Why waste time on me? I am afraid you will find me hopeless as I know you are. . . . Please go out and jump in a dust cloud around Amarillo and get choked. As for me I shall continue to be for soil conservation, and for the elimination of dust clouds—after you have been choked."

On one hilarious occasion a postal card arrived from San Antonio bearing openly upon its obverse such genial epithets regarding the Congressman's stand on the Supreme Court as the following: "mean and abject," "viper-like trespasser," "traitorous bid for personal patronage from the hand of one usurping the leadership of the Democratic party for a Fascist cause." To which Maverick replied in part: "You use language wholly improper for a gentleman—hysterical, even insane. In sending language which amounts to open libel and slander on a postal card you have committed a Federal felony for which you could be sent to the penitentiary. . . . You will regret mailing the card, not on my account but your own, for I shall do nothing and say no more about the mater. You are at liberty to show this letter to your friends." As the italicized sentence indicates, the Congressman is well aware that a red-hot rejoinder is seldom exhibited to others by the recipient.

It would be quite misleading, however, to rest the epistolary character of the gentleman from Texas upon the above bouquet of thistle blossoms. In the nature of the case answering a fool according to the nature of its content. To those who address him courteously, no matter how strong their opposition, he replies with courtesy, broad tolerance, and complete good humor. Always the replies are forceful, clearly expressed, and entirely unafraid. There are occasional stylistic slips such as occur in all dictated statements but, taken as a whole, they make it clear that Maverick regards letter writing to constituents as a fine art, practicing it not only skillfully but also with that restraint which is the first sign of the master.

"I should have lost," wrote Edmund Burke to his electors in the City of Bristol, "the only thing that can make such abilities as mine of any use in the world now or hereafter: I mean that authority which is derived from an opinion that a member speaks the language of truth and sincerity, and that he is not ready to take up or lay down a great political system for the convenience of the hour, that he is in Parliament to support his opinion of the public good, and does not form his opinion to get into Parliament, or to continue in it." Doubtless Maverick would find these sonorous words somewhat egotistical and stilted, even professorial. Ever since they were written, however, politicians and political scientists as well have been mulling over the question: "Whom should a representative represent?" It is doubtful if the gentleman from Texas has gone into the philosophy of the matter at all deeply, but on the basis of his own experience he has worked out a quite definite and practical answer which is fully in accord with the principles set down by the great English statesman. However, Maverick adds certain corollaries of his own. He holds himself bound to act on mandate as to things definitely pledged during a campaign. On the other hand, he does not consider himself bound in matters of fundamental national interest, nor in cases of sudden emotion or of mob violence which might occur in his district. "A man must have guts enough to fall out even with his friends." If a new political issue comes up Maverick considers himself free to take sides as his convictions dictate. In any event he holds that he was not elected to be a rubber stamp. Finally he is convinced that "the only way to play politics is not to play politics."

In his various campaigns Maverick has made abundant use of handbills but not of placards. It is his stump speeches, however, that are most effective; they are racy, pungent, humorous, argumentative, straight-from-the-shoulder affairs that carry conviction to the hearts of his hearers. Apparently they cost him little effort; not so, however, the speeches which he makes in the House. As part of the Congressman's "record" the latter are prepared with meticulous care. Braintrusters may be called in for research and verification. But Maverick himself writes out and revises every word he is to pronounce on the floor of Congress; afterwards he goes over the printer's proofs painstakingly two or more times. He is particularly effective in his opening words which are designed to outline what is to follow or to strike a keynote or simply to catch the attention of his colleagues. For example, on the Judicial Reform Bill, February 22, 1937, he began crisply as follows: "Mr. Speaker, I rise today to make one statement, two observations, and one conclusion." He kept his words exactly and, having good terminal facilities, finished in exactly four minutes' speaking time. If details are important he adds them under leave to print in the form of notes which often show wide reading and careful collection of data.

Again speaking for the Gavagan anti-lynching bill before the House in Committee of the Whole, April 15, 1937, Maverick began: "Mr. Chairman, I am from the South, and I never knew a Republican was white until I was twenty-one years old." Humorous claptrap perhaps, but it brought a laugh, captured attention, and was followed two seconds later by words the like of which are seldom heard on southern lips and which went direct to the heart of the issue: "I am in favor of an anti-lynching bill. I am not in favor of any Federal bill that takes over local law enforcement. But I am in favor of a bill which guarantees constitutional rights of all American citizens within the United States of America."

Maverick is as careful about the ordering as he is of the selection of his material. Here his newspaper training stands him in good stead. He seeks always to put his case first in the smallest possible number of words so that he who runs may read. Afterwards a more detailed argument is presented for the benefit of those who have the time and are more deeply interested in the subject. He avoids the arrangement of materials in those long, unbroken columns of fine print which make the Congressional Record so arid and repellent. Each text published by the Congressman is carefully subdivided; all the subdivisions are provided with captions, often striking in phraseology, which enable the reader to pick and choose at will. It would be difficult to find a better arrangement of printed material anywhere than in Maverick's brief report on the military disaffection bill. In addition he made a dozen speeches on the subject but it was this smashing report, widely publicized, that killed the bill.

While careful in all matters of form Maverick does not hesitate to resort to innovations. Brevity ranks high among them. People may once have had time to listen to speeches as long as Andy Smith's famous prayer but that day is past. Younger members of the House are lucky if they get ten minutes—and a very good thing that is, too, in Maverick's opinion. Reports should not be allowed to run to two volumes; eighty, ninety, or at the outside one hundred and fifty pages should suffice. Nominating speeches of the old-time variety which went on and on and on, without mentioning the candidate, and then attempted to reach a climax at the end with the naming of the "gr-r-r-r-eat leader" are particularly obnoxious to the Congressman. Nobody is ever surprised or thrilled and everybody is exhausted and exasperated when the wind-up—usually a sad anti-climax—is reached. If the gentleman from Texas has an introduction to make he names the man at once, briefly recites his qualifications—and sits down.

One of the most striking of Maverick's innovations was the publication of numerous book reviews in the sacred but abysmally dull pages of the Congressional Record. He was a trifle truculent in prefacing this device: "If I should call this an oration—and take five or ten pages of the Congressional Record, it would meet with the approval of everyone, because no one would read it. Hence if I choose to call what I put in the Record 'a book review,' that is my constitutional right, and not even a unanimous decision of the Supreme Court can take it away from me." Naturally with so large a chip on his shoulder someone was certain to make a pass at it. In the course of the next few days a certain well known writer on the Chicago Times observed that: "the jolly old Congressional Record has at last stooped to folly in its most verbose form—three columns of masterly literary criticism by the Hon. Maury Maverick of Texas on a government report entitled The Future of the Great Plains." Maverick responded by reprinting the criticism in full in the Record, and having thus used the publicity of the affair for all it was worth, continued calmly with the publication of further book reviews. In the opinion of the writer, who is not without experience along this line, they are, while somewhat given to unconventional turns of phrase, fair in judgment, admirably written, full of verve and humor, and certainly far above the average of the common run of stuff printed in the Congressional Record. Incidentally they have served to give publicity and wide distribution to several important government reports which otherwise would have rotted in the basement of some public building in Washington.

First elected to Congress, November, 1934, Maverick came to Washington the following spring merely as one of the 435 members of the House. Within a year he was nationally known, figuring largely in the news reports of the country as a whole. The New York Times, for example, devoted seventeen articles to his activities between March and September of his first year as a representative. How did he thus manage to emerge from the obscurity which envelops the doings of the average congressman? So many of them remain immersed in trivia, notables perhaps in their own districts but little known to the world outside.

In part the answer has been indicated already, Maverick possesses gifts of brain and heart that would make him a leader in any social group. Fundamental to the understanding of his career as these qualities are, still certain other details are not without significance. One may ask: "What's in a name?" with the usual scornful intonation given to that question, but it must be admitted that Grandfather Samuel Augustus helped considerably on this score. Maverick is a quaint enough cognomen in and for itself, but it is also one which, thanks to the said ancestor, had passed into general use as a common noun. Since the new member of the House who bore it hailed from Texas he must, of course, be "picturesque"; doubtless he wore chaps, spurs, bandanna and a ten-gallon hat; doubtless also he was full of the tall tales so characteristic of the wild and woolly Southwest. Deluded by these stereotypes, which by the way nauseate Maverick and all other good San Antonians, reporters and press photographers descended in a body upon the new congressman immediately after his arrival in Washington. They saw a somewhat stodgy person in conventional and none-too-good attire; but they did not get the tall tales they were after. As for the expected cock-and-bull stories about pioneers, about the fall of the Alamo, about deeds of derring-do in the great open spaces where men are men and all that sort of antiquarian rot, there was absolutely nothing doing. Instead they got the cold, unvarnished truth. One reporter more intelligent than the rest—at least he knew something about the importance of San Antonio as a military center—asked Maverick for his views on war. The answer to that question was NEWS; it was so forceful, so wholly unexpected. Subsequently reporters have always received the same frank treatment at the hands of the Congressman. It is evident that they like him personally; in particular they like his habit of laying all the cards on the table, faces up. Perhaps also they feel him to be one of themselves as a result of his journalistic training and experience.

More important even than his facility in relations with the press were Maverick's affiliations with like-minded younger members of the House. Shortly after he arrived in Washington they came together for the formulation of common principles and policies, adopting a vigorous and comprehensive sixteen-point program dealing with labor, agriculture, taxation, public works, monopolies, war, education, revision of the rules of the House, free speech and free press, and with sickness, old age and unemployment benefits. [For a more detailed statement of these sixteen points see the New York Times, March 17, 1935.] Since that time these independent younger members, reinforced by several veterans of the House, have held together, fighting pertinaciously for the ends they have in view. [Among other members of the group the following may be mentioned: Jerry Voorhis, Charles Colden, Ed V. Izac and Byron N. Scott of California; John A. Martin of Colorado; Kent E. Keller and Frank W. Fries of Illinois; E. C. Eicher of Iowa; John Luecke of Michigan; John T. Bernard of Minnesota; Herbert S. Bigelow of Ohio; Sam Massingale of Oklahoma; Robert G. Allen, Michael J. Bradley and Charles Eckert of Pennsylvania; Fred H. Hildebrandt of South Dakota; W. D. McFarlane and Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas; John M. Coffee, Knute Hill and Charles H. Leavy of Washington; and George J. Schneider of Wisconsin.]

Now these independents, judging by the impression they have made in national affairs, "have what it takes." They do not care a tinker's damn what they are called, regarding the use of epithets as very old-fashioned reactionary technique. Just the same if any misguided opponent so far forgets himself as to dub one of them a demagogue, the honorable gentleman concerned is quite likely to demagogue him right back as a "Country Club Communist," adding sufficient detail to keep the said misguided opponent busy explaining to his constituents that he is nothing of the sort for a month or more. Nor do the members of the younger congressional group waste any time finding names ending in "ism" for their movement. "Liberalism"? In their bright lexicon that means too much—or perhaps nothing. "Radicalism"? They have broken with the old timers of that school who were forever shouting denunciation of Wall Street and never doing anything about it. "Socialism"? No; they regard the doctrines of Saviour Marx and Apostle Lenin as little relevant to the American scene. Congressmen of the new type are inclined to laugh at the soap-box rabble-rouser who always signs himself "Yours for the Revolution." They are convinced that the problems now before the country are not going to be solved by physical force; they have a deep underlying faith in scientific research and in democratic processes. On the other hand, they will tell you frankly that they regard the Constitution as having been made to meet human needs, and hence requiring amendment as conditions change. Rigidity they regard as the one most dangerous political condition. They have not the slightest intention to confiscate wealth but they do mean to distribute property rights widely. If this be treason—or Radicalism, or Socialism, or demagogy, or what have you?—very well, then, you can make the most of it.

Maverick's attainment of national prominence within a year after he came to Washington was not due to work on his part toward that specific end. Rather it came about because he just worked, to the full limit of his forces, for the things which he knew needed to be done. There is, however, an essential logic in the nation-wide distinction he has gained. Essentially he is neither the local nor state type, not even the sectional type, of politician. He approaches issues from the point of view of the country as a whole; hence his actions and utterances make an appeal everywhere. Considering that the Congressman comes from below the Mason and Dixon line the absence of sectionalism from his make-up is particularly noteworthy. As a matter of detail in this connection, even his alleged southern intonation is only faintly if at all perceptible. It is not that he lacks interest in the problems of the South. On the contrary he is acutely conscious of them, particularly in such matters as soil reclamation and conservation, wages and wage differentials, housing, and the like. What he aims at, however, is not sectional welfare per se but rather to raise his section together with the country as a whole out of depressed conditions. As a corollary of this realistic national approach to southern problems Maverick loathes the old-time, moonlit, romantic, chivalric, dear-old-black-Mammy, magnolia-and-honeysuckle-blossom, so-red-the-rose-gone-with-the-wind type of fiction. One exception may be noted: the Congressman admits a certain regard for the honeysuckle. Not based either on scent or sentiment, heaven forbid, but solely on the fact that soil conservationists have found it "an effective gully control plant."

No attempt to account for the achievements already to Maverick's credit would be complete without mention of the fact that on May 22, 1920, he married Terrell Louise Dobbs of Groesbeck, Texas. "We are still together," he remarks somewhat whimsically in his autobiography; still, when one recalls what happened to so many marriages contracted in the tangoing twenties, perhaps such a fact does need to be recorded. Very much "together" also, judging by his wife's activity as helpmeet. Both as gracious hostess in their home and as efficient assistant in his office during occasional rush periods, Mrs. Maverick has contributed greatly to her husband's popularity. They have been joined by a son, Maury, Jr., born in 1921, and by a daughter, Terrell Fontaine, born in 1926.

As to physique one does not have to be an astrologer to read in the stars that Maverick was born under the sign of Taurus. Nor a genealogist to perceive that he possesses the bodily traits implied by his family name. There is a tremendous latent strength, slow-moving but persistent, in the man. Height, a trifle under five feet, eight inches; avoirdupois, perhaps the less said the better, however he does fall within the famous dictum sponsored by former Speaker Thomas B. Reed. viz.: "No gentleman ever weighs more than 200 pounds." If there is too much adipose tissue especially around the girth, the result of sedentary life and lack of exercise, there is also plenty of bone and sinew. Maverick's shoulders are well set and powerfully muscled arms long and brawny; hands—democratic hands with short, stubby fingers but capable of a tremendous grip; legs short and massive—one fancies them slightly bowed from interminable hours in the saddle during boyhood. Despite the burden carried the Congressman's gait is jaunty enough.

Cartoonists dealing with Maverick's head seize instinctively upon the heavy tousled thatch of wiry, dull-black hair. It can be made to lie flat at the back and sides but toward the front it shapes itself naturally into rebellious, wave-like rolls which bend first forward, then upward and back, the one immediately over the forehead especially protruding and giving the effect of a small plume. The brow is broad rather than high. Nose a sharply defined equilateral triangle, not the long, thin nose of a philosopher but fleshy and with a pronounced thrust en avant, inquisitive, penetrating, and pugnacious. Eyes slightly protruding and gray with a scarcely perceptible greenish glint; they look out on the world for the most part in a rather cool and speculative manner. Mouth firm and well rounded; full lips often puckered in thought; aggressive, fighting chin. On the whole a good poker face; but Maverick has never played the game, "too busy ever since I was born" and does not know one card from another—thus one more cherished illusion about Texas is shattered! In spite of his ordinarily serious expression the Congressman is quite capable of an engagingly boyish grin over an amusing episode or story.

As to dress, careless comfort and quiet colors seem to be the ends aimed at although it is doubtful whether Maverick ever gives the subject a thought. To say that "he looks as if he slept in his clothes" is putting it too strongly. His manner as a rule is almost Quaker-like; when strongly aroused, however, there is no lack of animation. Standing before a fireplace discoursing on the Supreme Court he sweeps all the Nine Old Men from the high stone mantel to the floor with a single vigorous gesture. His voice is always well controlled; in conversation it is low-pitched, unemotional but persuasive; in public addresses he can use it to meet any mood on the part of his audience and to fill resonantly any hall, no matter how large.

The general physical impression, that of a steady uprush of inexhaustible energy, if verified by Maverick's capacity to put in day after day of grueling labor, eighteen hours out of the twenty-four, for months on end. Obviously this is a pace that cannot be kept up indefinitely. It is true that political work is always fascinating and frequently amusing to the Congressman; in a sense he makes play out of it. On the other hand, the word "recreation" is simply not in his vocabulary, a dangerous oversight; he even seems embarrassed when it is mentioned and seeks to excuse himself by saying that, when not busy in Washington, he enjoys making field-surveys of his dearly beloved reclamation schemes, of housing projects, of the TVA dams and power-plants, and of government works generally. (At this point, feeling that his self-justification is complete, he remarks that it would do the justices of the Supreme Court a world of good if they were to follow his example, thus learning something about American life as it is actually lived, instead of slumbering away four long months each summer in various pleasant country retreats.) When the Congressman's attention is once more drawn tactfully to the fact that field-surveys are also work and that he has not so far put in evidence any real recreation on his own part, he mumbles something rather sheepishly about his small farm with its street car home perched on the hills above San Antonio. There at rare and all too brief intervals he potters around, looks after his fruit trees, escaping the sun in their grateful shade—and lets the world go hang. It is a curious quirk of the man, however, that while he himself scarcely ever stops working he is profoundly convinced that "America must learn how to use its leisure time."

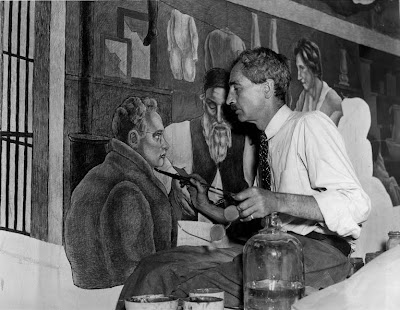

Maverick's office, Room 101 of the Old House Office Building, is a favorite port of call not only for politicians but for all the newshawks of Washington as well. It is essentially a man's workshop; there is nothing sissified about it, no spick-and-span furnishings, no flowers on the desk, no lady secretaries à la mode to do the honors and give a tone of refinement to the place. Chairs, tables, and bookcases are heavy and serviceable. There are, ahem, one or two brass cuspidors on the floor—solely for the use of certain visitors; otherwise, of course, it would not be a real politician's office. On the walls a motley array of maps, plans, photographs, and engravings. Among Presidents, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, and Johnson look down upon the busy scene; in a place of special honor there is a photograph of Franklin D. Roosevelt warmly inscribed to the Honorable Maury Maverick. Interspersed with the foregoing there are cartoons dealing with recent political happenings, drawing which present realistically the life and labor of the very poor, a wall map showing the WPA in action, engineering plans of great national reclamation projects. An incongruous note is supplied by the picture of a squadron of military airplanes in flight among the clouds. However, it is balanced by a reproduction of Constantine's gruesome painting, "Battle's End," which shows a young soldier, wounded and mud-stained, who has dragged himself to die in the midst of a graveyard. Close by one sees a small blackboard on which are noted the days and hours of Maverick's engagements at the House Gymnasium, most of these followed by a zero to indicate that he had cut class. Books, books, books, among them many presentation copies, stacked on tables, desks, and shelves, the great majority being recent publications in economics and political science, precisely the sort of reading on which college professors of these subjects are now engaged. On the floor in various places, convenient or inconvenient, great piles of public documents for consultation or for mailing out to constituents. Decidedly this is an office which reflects the character of its occupant.

On the basis of Professor Charles E. Merriam's analysis of the qualities most frequently exhibited by political leaders, it is evident that Maverick would receive a grade—if one may speak in that professorial jargon which he abominates—of "A" or at least of "A—." [See Charles E. Merriam, American Party System (rev. ed. New York, 1929), p 48.] Unquestionably the gentleman from the Twentieth Texas District possesses unusual sensitiveness to the strength and direction of social and industrial tendencies, always, however, with particular reference to their effect upon the underdog. He is politically inventive and quick in putting his inventions to work. In group combinations and compromise his success at Washington has been noteworthy, although here perhaps he is more inclined to belligerency than to caution. As to political diplomacy in ideas, policies, and spoils, the first two rate an "A+," but the third must be marked "D—," although this is everlastingly to his credit. Maverick possesses marked gifts in making personal contacts, also facility of the highest possible order in dramatizing the sentiments and interests of large classes of voters. As to "courage with a dash of luck" the former is his in superabundant degree; regarding the latter he opines that he is indeed lucky since he just missed getting killed several times in battle and later in a number of the automobile accidents of peace time. To the objection that this is a rather negative conception of what constitutes good fortune his reply is: "Never got anything worth having by luck; always by hard work and plenty of it."

With so much already achieved, what of the future? If he cherishes ambitions Maverick does not worry about them. What he wants is to do a good job now. Granted that, the future can safely be left to care for itself. In any event he wishes no preferment which would inhibit his personal independence. Certainly Maverick is not one of the type of politicians classified by Professor Merriam as "power-hungry." On the contrary there is nothing of the pride of place in his demeanor: to use a homely phrase he is "as easy as an old shoe." One can imagine his raucous laughter over the pretentious, know-it-all "statesmen" still so common in Washington. Of an essentially combative nature, to Maverick the fight's the thing in large part, victory or defeat mere incidents of slight consequence. Yet he rejects Nietzsche's dictum that "a good fight hallows any cause." Rather he holds a draconic conviction of the justice of his cause and hence of its ultimate prevalence. Above all, his profound sympathy with the poor and underprivileged and his even more profound belief in the possibility of social meliorism through democratic processes are the prime motors of his every action. He knows the world is out of joint but thinks it no cursed spite that he has been called, so far as his powers avail, to set it right. On the contrary, this should be the highest duty and privilege of all men who are strong and intelligent not only, but humane as well. To a very large degree Maverick painted his own portrait when he inserted in the Congressional Record the stirring words of Louis Untermeyer's "Prayer":

On another occasion when the news of Hitler's burning of the books was still fresh, Charles A. Beard, dean of American historians, was being interrogated before the same Committee, although the word "heckled" would describe the process more accurately. Because of his partial deafness the eminent scholar was at a marked disadvantage. Scenting an easy kill, one of the more militaristic members of the Committee started in full cry, his eyes gleaming, his nostrils quivering. And the object of his relentless pursuit? Ah, my friends, it was COMMUNISTIC LITERATURE, nothing less—and nothing more definite, either. He wanted to know all about it; in fact he clamored—and yammered—at great length for knowledge, meanwhile doing his utmost to browbeat the witness. Most of all he craved to learn in what libraries such dastardly literature was concealed. Whether or not the Professor grasped this particular question, his mild answer was: "In all of them, I should think." To which Maury Maverick added, again ending the séance: "No doubt there's plenty of it in our own library, the Congressional Library. Does the honorable gentleman desire to have it burned down also?"

Unquestionably, given a good cause, the gentleman from Texas dearly loves to upset the apple-cart. And nothing affords him more joy, holy or unholy, than to deflate stuffed shirts, especially when enveloped in military uniforms, as sometimes happens to be the case. In so doing, of course, Maverick runs the risk of gaining the reputation of an enfant terrible, or, worse still, of a recognized congressional wit. The latter is, perhaps, the saddest of all legislative fates, as the career of "Sunset" Cox demonstrated a generation ago. That the gentleman from Texas has escaped such a nemesis is not due to any lack of humor, mordant or otherwise. It is due to the fact that he does not stop with the outburst of ready laughter. Attack with words, whether humorous or with "tough, hard, mean words"—to use his own expression—is always backed up by serried masses of facts, laboriously collected, meticulously ordered. And facts are also "tough, hard, mean" things. To illustrate and at the same time to revert to the two incidents narrated above Maverick kept up the fight until he had killed the Military Disaffection Bill. He is still prouder of that success than of anything else he has accomplished in Washington. And that in spite of many notable achievements which bulk much larger as matters of public business and which have reverberated resoundingly through the press of the country as a whole. For example, his fights for the conservation of natural resources—the matter which is always foremost in his thought, for housing and slum clearance, for the TVA, for mandatory neutrality legislation, and more recently for the reform of the Supreme Court are not likely soon to be forgotten.

Maverick was born at San Antonio, Texas, October 23, 1895, the eleventh and youngest son of Albert and Jane (Maury) Maverick. English, Scotch-Irish, and French Huguenot stocks—a strong and typically American mixture—are all represented in his ancestry. It is impossible to talk to the Congressman for any length of time without discovering that he is enormously interested in the history of his family, a trait which, by the way, is abundantly manifested in his recent book, A Maverick American. At first sight it would seem to indicate that the gentleman from Texas shares the aristocratic outlook supposedly cherished by all members of "fine old Southern families." Twitted on this score, so incongruous with his extreme democratic outlook, Maverick defends himself with a certain show of indignation. He assures you that he is "an ordinary man with ordinary ideas" (which, with all due regard to his sincerity, is simply not the case); further, that so far as he can discover all his ancestors were of the same type. In other words, all the Mavericks were mavericks, i.e., commonplace men and women more or less astray in the midst of the social and economic forces of their time. Regardless of the tie of blood the Congressman assures you that he can see their vices and failures just as clearly as he sees their virtue and successes. Finally—and make no mistake about it—he studies their past struggles not because of any aristocratic feeling but solely for his own guidance amid the dominant forces of the here and now.

An ingenious theory, this, to dispose of the charge of ancestor worship. Nor can it be dismissed out of hand as rationalization, pure and simple. Still it is apparent that Maverick admires his forbears as a whole, particularly those who were on the popular side in the political conflicts of their day. Unquestionably also he takes a certain sinful pride in their fighting qualities, regardless of the side on which they fought. Chalking up this minor demerit—if demerit it be—against the Congressman, it must be admitted in his favor that his extended genealogical researches have given him an unusual knowledge of the history of the country and particularly of the South as seen from the viewpoint of human mavericks. Whether his ancestors were conservatives or radicals—mostly they were the latter—it is true that he studies them always from the point of view of the problems he is trying to solve today. One of the most characteristic features of A Maverick American is the way in which the author after describing briefly the exploits of some colonial or revolutionary ancestor, proceeds to apply at length the lessons thus learned to the matters he has now in hand, for example, to soil conservation, militarism, taxation, poor relief, and the like. Decidedly Maury Maverick is a much more effective and a much more down-to-the-minute political leader because he has forgathered so extensively and so intimately with his forbears.

In his political career the Congressman is under particular obligation—as will appear later—to his grandfather, Samuel Augustus Maverick. It was because of this gentleman's easy-going management of his ranch that the name "maverick" came to be applied to unbranded, roaming cattle. To his father and mother, however, Maury's indebtedness is beyond all computation. They seem to have been ideally fitted for parenthood; moreover they had had plenty of practical experience in child psychology before the birth of their eleventh and last child. In the charming picture which the son paints of their life together, characteristically using political colors, the mother is portrayed as a shrewd and active prime minister, the father as a quiet and kindly constitutional monarch. Tolerance reigned in their household; frankness and fearlessness were the order of the day. Here the twig was bent; so the tree is inclined.

Educational life on the whole proved much less satisfactory than family life. Young Maury came up through the public grade schools and the High School of San Antonio; for some reason undisclosed he notes: "did not graduate from the latter." Indeed he seems to have made a specialty, then and latter, of dodging graduation. Which, of course, now leaves him wide open to the offer of an honorary degree. (Which, probably, he would decline.) There was a rather ineffectual year at Virginia Military Institute; after that, three "wasted" years at the University of Texas, where he enrolled for journalism. Again the notation: "did not graduate." This time the reason was that Maury found himself overpowered by a desire to practice law, probably with some thought of politics in the offing. As a result he set himself the strenuous task of doing the three years' work of the law school in one year. And a third time he "did not graduate." However, he won admittance to the local bar and threw himself into practice with the ardor characteristic of him when he is really interested in what he is doing.

One of the commonest obsessions of college men who have reached middle life is that during their undergraduate year they were regular hellicats. As a moral equivalent or sublimation for raising Cain after the time for that sort of amusement is over and done, this trick of memory probably has a certain ethical value. Curious, however, that a man so shrewd as Maverick should be subject to it. As foundation for the delusion he adduces nothing more conclusive than the usual catalogue of student sins—cutting, activities, college politics, membership in an organization known as the Campus Buzzards, drinking, brawling and disorders on the campus, run-ins with the deans, and so on, and so on. (No mention of "fussing." Why not? Texas was coeducational.) On the other hand, Maverick admits that during his high school and college years he was an omnivorous reader, particularly of "banned" books. As this was before the days when sex was discovered apparently these latter were for the most part treatises on ethics, philosophy, and sociology of which professors disapproved. Or said they disapproved. Experienced college instructors will recognize the device, which is at least several centuries older than Machiavelli. As they well know, nothing so whets the curiosity of an undergraduate as to tell him that he ought not read a certain book. Whether so intended or not in the present case, young Maury swatted up vigorously all prohibited literature; thus even when in college his education was largely self-administered. Evidently his intellectual curiosity was insatiable. Given a really understanding tutor he would have forged ahead at a tremendous intellectual pace. As things were, he did indeed make direct use of the instruction given him in journalism. On the other hand, he took no courses in economic or political science. Owing to his prejudice against professors Maverick is rather loath to admit being influenced by any of that tribe. Under pressure, however, he does pay handsome tribute to Edwin DuBois Shurter, now retired, whose instruction in public speaking, particularly in the matter of logical and effective presentation, has been of the greatest possible utility to him throughout his political career. And in general Maverick acknowledges the value of university training even if most of the courses in his time were dull and tiresome. One detail of his educational experience is not without distinct political significance. Since the University was located at Austin, students had an excellent opportunity to observe state government in action; also to meet personally the present and prospective leaders in Texas affairs. As a piquant detail he notes that many members of the legislature were attending the law school, adding "so we frequently attended the State Legislature."

It was by no means certain that Maverick was predestined to politics, highly gifted for that pursuit as he has shown himself particularly since entering Congress. Various other alternatives were first explored and eliminated. Thus he might readily have gone on with journalism for which he was trained at the University of Texas and which undoubtedly he would have been brilliantly successful. Already at the age of eighteen he had secured a temporary job as city editor of the Amarillo News which he enjoyed hugely. After completing his work at the University he made rapid progress as a lawyer and was elected, partly as a result of his popularity among younger members of the profession, partly because of some shrewd political maneuvers, president of the San Antonio Bar Association at the age of twenty-four. It is clear, however, that the detail of legal practice is as repellent to him as it was to the young Theodore Roosevelt, whom he resembles in many other respects. Moreover he did not like the idea of prosecuting criminals; he "always felt sorry for the defendant." One other profession to which he devoted himself temporarily, that of the soldier, would have proved impossible in the long run. For an individual so wholly dedicated to the love of liberty as Maverick is, life under military discipline is unthinkable. Nevertheless he enlisted promptly after our entry into the World War, served with distinction as lieutenant of infantry in France until desperately wounded, October 4, 1918, and was awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart medals for gallantry in action. Of this experience, to which he devotes thirty of the most poignant and brilliantly written pages of A Maverick American the principal results were the knowledge of war and the hatred of it which are the strongest of his intellectual and emotional drives to the present day.

Following his excursion into legal practice Maverick discovered, somewhat to his own surprise, that he was a business man of sorts. He made money hand over fist in lumber and building; indeed his conscience troubled him not a little at the ease with which he could run up jerry-built houses for $800 or $1000 and then sell them out of hand for twice as much. Quite apart from such scruples, however, it is clear that wealth makes little appeal to him. From his successful building experience, however, Maverick did derive one result of permanent political value, namely a thorough practical knowledge of the housing problem in the United States. And that problem has ranked high among his preoccupations as a public man ever since.

Considering the number of vocational bypaths Maverick explored, one may well ask: "Why, then, the ultimate decision to enter politics?" Partly, as we have seen, because of ancestral tradition. It cannot be maintained, however, that immediate family environment predetermined his choice. True the Mavericks had the advantage of being "old settlers"; moreover it is not without political significance that the Congressman himself has maintained a residence in the San Antonio district throughout his entire forty-two years, and in his present residence for ten years. Of living relatives, however, only one, an uncle by marriage, had been a congressman. There was, of course, the glowing memory of the grandfather, Samuel of cattle fame, as a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence back in 1836. While other more distant relatives had held local offices on up to a governorship or two, still the great majority of them had been soldiers, sea captains, merchants, and plantation owners.

As to the dawn of political consciousness Maverick is quite definite. It occurred at the age of six when President McKinley visited his home, evidently making a tremendous impression on the boy. Subsequently he was to meet Bryan under his father's roof, and elsewhere La Follette, Victor Berger, and Eugene Debs, all of whom he admired apparently in proportion to their radicalism and forthrightness. And, of course, he met many Texas worthies including "Pa" Ferguson, who despite his demagogy "had a heart" and also the guts to fight the fire of the K. K. K. with an even hotter backfire; also George C. Butte, professor at the law school of the University, whom Maverick was to support some years later in his candidacy against Ferguson. Undoubtedly this range of political acquaintance, extremely wide for one so young, was potent in turning his thoughts toward a public career.

If the young Texan was predestined to politics it was, however, neither family, nor education, nor acquaintance which decided the matter. Rather he was driven by his social consciousness, or, to avoid professorial words abhorrent to the Congressman let us say he was overpowered by the true maverick spirit, namely by deep sympathy with the multitude of those who were astray and neglected. The most distinctive thing in his whole earlier life was his assumption of the role of a hobo during the last years of the Hoover regime when there was no relief and when, as a result, thousands of "transients"—human beings, not lost cattle—were drifting aimlessly and in dire misery through the vast reaches of Texas. To study their plight he dressed the part, not a hard job for him; he lived with them in "jungles" and flophouses and on the open road, incidentally becoming lousy in the process. But he did not stop with the mere accumulation of sociological data. Acting on what he had learned at first hand, he established a co-operative colony for transients at the edge of San Antonio which did excellent work until government relief began. In itself this experience may have been of minor importance. But it is vastly significant as to the springs of action which move Maverick. In times of profound distress a man with his deep humane feeling simply must leave all else and go into politics in the effort to set things right.

Second only to this fundamental emotional drive, Maverick had to go into politics because of the urgings of his intellect. Nourished by ceaseless reading of economics and political science, he knows that he can set things right, some things at least, if power be given to him. And he means to do all that is in him to that end regardless of opposition and objurgation. Those mistake the man utterly who point to his alleged demagogy as a basic trait of character. "I may demagogue," he observed, using the word as a verb after a fashion coming into vogue in Washington, "but never on any matter of importance." Really all that it means to him is nothing more than an occasional resort to sensationalism in order to arouse interest and secure support. Back of all such superficial manifestations there is a cool, disciplined, and informed intelligence of the highest order. Also an inflexible determination to tell the truth and shame the devil, regardless of the cost to his own political career.

No doubt it will grieve the Congressman sadly, but it must be said that, much as he affects to deride professors, he possesses many traits of that species. True he does not speak their "jargon"; that would never do since he has to run for office from time to time. But he does read their books continually, translating them into bills, also into speeches for both congressional and popular consumption. [For example, his H. R. 7325, 75th Congress, 1st Session, introduced June 1, 1937, providing for the creation of an Industrial Expansion Board and other Federal agencies, represents a painstaking effort to create the administrative machinery necessary for the carrying out of the principles of Mordecai Ezekiel's profoundly significant book entitled $2500 a Year.] He does work the Congressional Library overtime, particularly the Research Division. He does write book reviews, even publishing them to the Congressional Record. He does contribute frequently to such high-brow journals of opinion as The Nation and The New Republic. He does call continually upon braintrusters for research assistance, sometimes putting two of them at work, unknown to each other, on the same problem in order to compare their findings. He does annotate his short, short speeches with long, long footnotes full of details, a professorial habit if there ever was one. He does make the damaging admission in A Maverick American that "the march of the professor is the greatest advance in the history of our government." Finally, as the Swarthmore address showed, he does love to talk to students. It was, in fact, a typical academic lecture even to the characteristic fault of such discourses, the effort to cover too much ground. Also Maverick sent several thousand public documents to the College beforehand, asking that they be distributed to students in preparation for his speech. In other words, professorial words, "collateral reading" if you please.

Although he had interested himself in civic affairs for several years Maverick's actual entry into politics did not occur until 1929, when he ran for the office of tax collector. To the surprise of the wiseacres he was successful against a city-county machine previously considered impregnable. Two years later he won his re-election against the same opposition. It is rare indeed that the personal popularity of tax collectors increases during their term of office. Nevertheless in 1934 Maverick was elected to Congress after two bitter Democratic primary campaigns in which he defeated the Mayor of San Antonio. Again in the primaries of—final elections being virtually uncontested south of the Mason and Dixon line—Maverick received a vote nearly equal to that of his two opponents combined (Maverick, 21,703; Seeligson, 14,378; Menefree, 7,606), and a plurality twice as large as that by which he had won the nomination two years earlier. These figures are the more remarkable because the San Antonio district, unlike the overwhelming majority of those in the South, has been carried by Republicans at least half the time during recent decades. [In the primary of July 26, 1938, Maverick was defeated for renomination to Congress by an eyelash, his vote being 23,584 to 24,059 for his opponent. Perhaps the most striking feature of his campaign was the large amount of publicity it received throughout the country. It is seldom indeed that a mere congressional primary is thus treated as a matter of national interest. Maverick made a strenuous fight and took his defeat philosophically. To him it was merely the end of a round, not the end of the battle. Given his ability and energy one may confidently expect him, after a brief, well-earned rest, to resume his activities upon the stage of national politics.]